In this 2022 year, I would like to share those glimpses from Western Ukraine as part of Fotografia Zeropixel group exhibition ‘Spaces’ in Trieste, and also online.

In 2015, out of the blue, an email from my uncle popped up. Attached were the scans of four postcards sent by my grandfather’s mother from Crimea, shortly before it was occupied by the Nazi Germany in October 1941. It was the first time I heard about her. She had a name, Natalia Blumenfeld. She was a piano teacher. A day later, at a birthday party in London, I met a Ukrainian musician Olesya Zdorovetska. 6 months later Olesya invited me to the annual Lviv Book Forum. On my mind were the Crimean postcards, the annexed Crimea, the war in Donbass, as well as my own forgotten childhood visits to Lviv and the Carpathian Mountains. After years of wanderings, it felt like I was getting closer to connecting the dots within the European landscape, my European landscape.

I explored the Lviv cobble streets, peeped into the courtyards, climbed onto the roofs, wandered in the cemeteries, took a train to the Carpathians. At the Book Forum Olesya bought a collection of poetry by Debora Vogel, a female writer, art critic and intellectual of the interwar avant-garde milieu, who wrote in Polish, Hebrew and Yiddish and possessed a complex identity, much like that of the city itself, who perished in Lviv ghetto in 1942 and remained in obscurity for a long time. Vogel became the muse for our multimedia project Fragments of Memory that explored the complex relationships we have with the spaces we inhabit.

Lviv-Lwów-Lemberg-Lvov-Leopolis changed my perception of history. History no longer belonged to the textbooks, to something frozen that ended in the past, but alive and continuous.

One of the project contributors articulated Lviv’s uniqueness: ‘This city has a neutron bomb effect: about 98% of its houses survived, while over 90% of its population, the social fabric of the city, were utterly devastated. Forceful change of borders, occupation, Holocaust and Soviet deportations have changed the population of the city. We know instinctively the meaning of the term “displaced persons”, as we here are all descendants of these people.’

It is now 2022, the year marked by displacements, destructions, violence of Russia, the land of my birth and youth, in Ukraine, the land of my ancestors and of my contemporaries. Lviv became a key staging ground for refugees. Dozens of thousands were arriving every day. Some continued to Poland, Slovakia, Hungary and onward to the rest of Europe. Some stayed in Lviv.

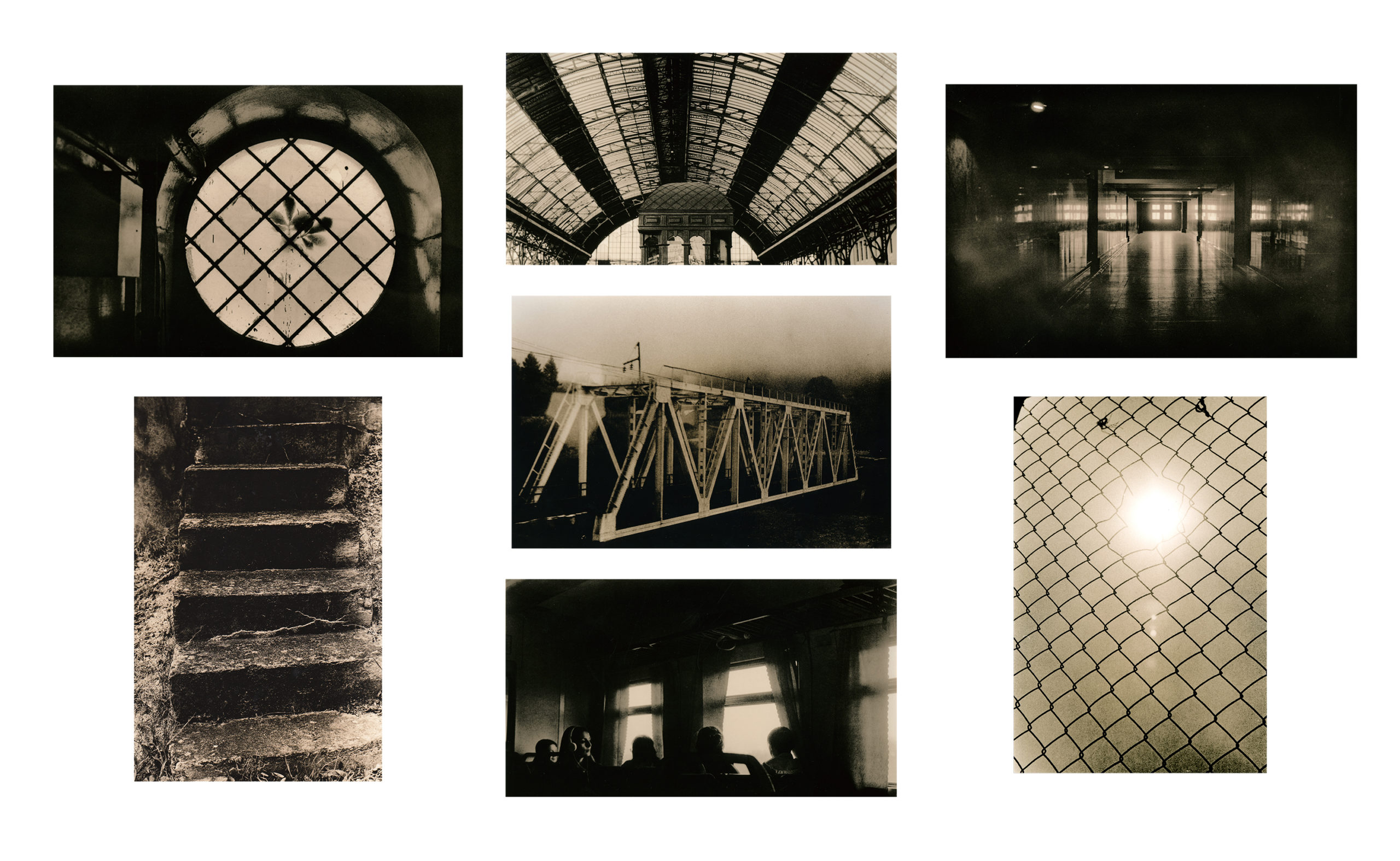

I’m looking at those 2015 glimpses and trying to imagine the spaces and the people in and around them – a rosette window in the 1913 Austro-Hungarian building, a 1904 art-nouveau railway station, a train carriage, a bridge, an old staircase in the multi-faith cemetery, a wire-mesh fence with the rays of sun shining through. Residential buildings, train stations, bridges are being bombed. Spaces are witnesses. Spaces remember.