Chapter 1 – Silence

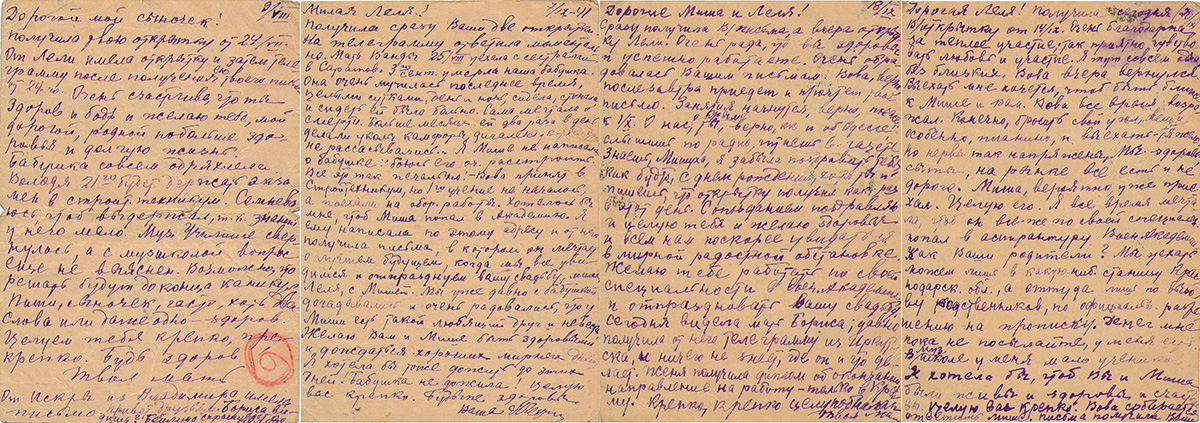

One day in 2015, out of the blue, an email from my uncle popped up. Attached were the scans of four postcards sent by my grandfather’s mother from Crimea, shortly before it was occupied by the Nazi Germany in October 1941. It was the first time I heard about her. She had a name, Natalia Blumenfeld. She was a piano teacher.

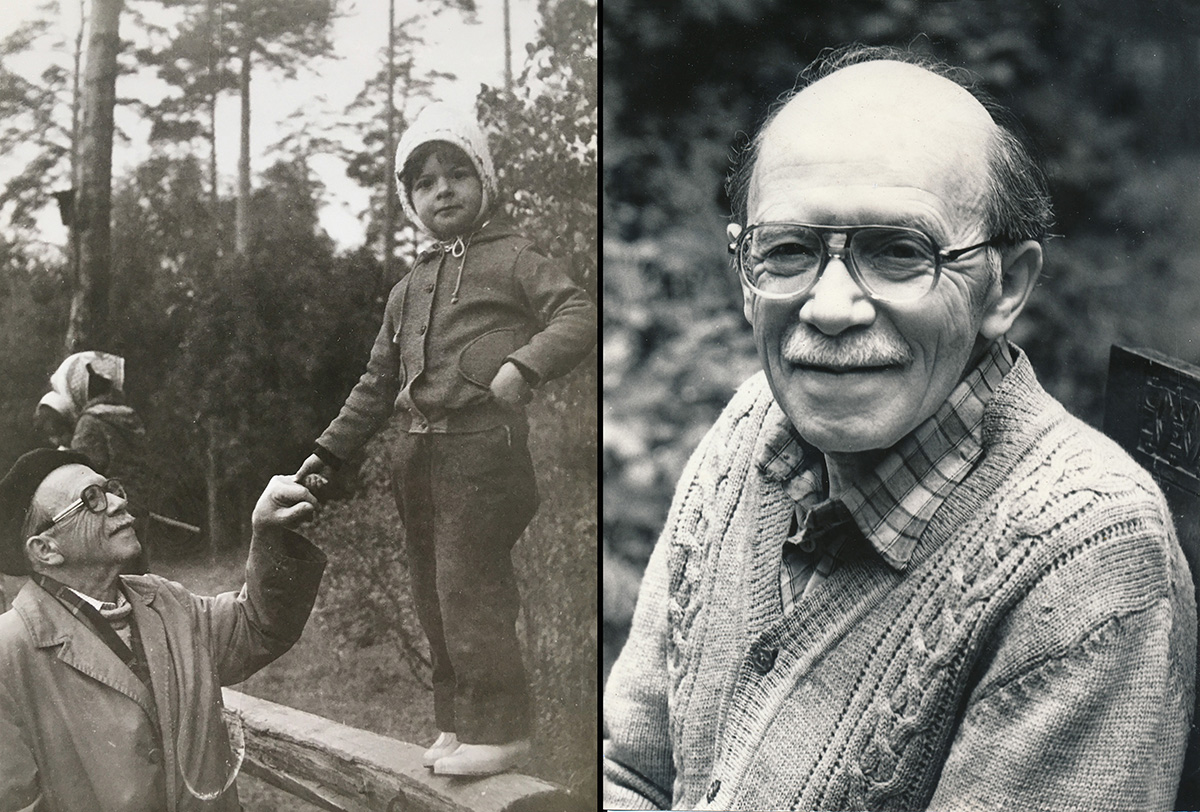

I have known Crimea since my childhood. Several years before then I was visiting a friend there. I went for long walks in the mountains overlooking the sea. I photographed and thought about my grandfather, Mikhail Gefter, who grew up in Crimea. What was it like? I knew so little about his early years and so my imagination filled the void. I returned to London, made darkroom prints and put them aside.

5 years later history changed again.

Russia invaded Ukraine.

Crimea was annexed.

What I knew about my grandfather was that he was born and raised in Crimea, left in 1936 for Moscow to study history, graduated on the eve of the WWII, volunteered for the front, was wounded twice, in later years became a dissident historian. I asked my father to tell me more. I learnt that on moving to Moscow my grandfather lived with his uncle David Blumenfeld and his family. In 1937 David was arrested and perished in Stalin’s purges. My grandfather’s mother and David’s son were killed in the Holocaust in Crimea. Nothing was known of his father, just a name, Yakov. Apart from those dry facts there was nothing. My grandfather never talked about his family. My father and uncle never asked. Neither did I. When the question popped up in my head, my grandfather was long gone. His historical and philosophical writings, video and audio interviews, hold no family stories, no documents, no photographs of the pre-war world.

It took me many years before I came to name this absence, this silence, as an inheritance of trauma––or more precisely, as both an inheritance of trauma and a traumatised inheritance. The traumas are multiple, including the Holocaust, the political killings of the Stalinist period, military and civilian death in war, forced migrations and displacement, and not least, the cultures of hiding that have grown up around these events. In time I realised that my grandfather had his own silences he could not face, and he seeded those silences as part of the culture of family life. This family culture was connected to larger forces of social and political culture in soviet and post-soviet worlds. Those postcards from Crimea were the first meaningful cracks in the silences. The authors Aarons and Berger of the ‘Third-Generation Holocaust Representation’ write that “a compulsion to ask questions in an attempt to reconstruct history, even in the face of the obvious knowledge that such queries will result in still more unanswered questions, is a symptom of the attempt to master the sensation of loss, to control, as it were, the traumatic outcome.”

In the beginning silence felt like nothing, like an empty vessel to be filled. In the process I discovered that silence was not disappearing with gathering the information, it could not be overcome, but travelled through. The research became a vehicle through the silence. The archive became a place where the textures of silences could be discovered. I learned that silences could be of different qualities and volumes, that there was as much variation in silence, as there was in speech. I learned to differentiate gaps, openings, and uncertainties, learned to ask questions. And those questions started opening closed doors.

Soon after I came across my grandfather’s interview from 1989: “We aim to learn seemingly everything about the lives of people who lived before us, or about our own lives. But we do not know beforehand, that we would not be able to find out everything. Either way we are making a selection. And at the same time this is our choice: by choosing from what was before us, what entered us as ‘past’, we choose who we are. And by choosing ourselves, we choose our future, consciously or subconsciously.”

It felt like my grandfather, who never spoke to his sons of the past, was addressing me now. Unlike Lot’s wife, I felt that I would run the risk of turning into pillars of salt if I did NOT look back.