Last month I reconnected with the places of my childhood holidays – Lviv and the Carpathian mountains in Western Ukraine. This area (former Galicia) was for centuries on the crossroads between Middle and Eastern Europe, and so it is small wonder that it has become a melting pot of people and cultures – Ukrainian, Jewish, Polish, Armenian, Belorussian, Lithuanian, Romanian, German.

The outbound trip started with an early flight from Stansted to Rzeszow (the most south-eastern Ryanair destination town of Poland) followed by a 2hour bus journey to Przemyśl. There I found a cozy little cafe with the titles of dishes scribbled on the wall (in Polish only) and after a few minutes of hesitated multi-lingual interaction I was presented with some superb soup followed by a much needed delicious coffee. Next leg of the journey involved a mini-bus to the Polish-Ukranian border that I crossed by foot. All that was rather emotional for me – as a 14-year old I crossed the border of Ukraine and Slovakia on my first Russian passport (Soviet template actually). It was my first ever time travelling to *Europe* and the excitement was overwhelming. Now, 20 years later, I was travelling the opposite direction on my British passport reliving childhood memories in the light of two decades of wanderings. I boarded another mini-bus on the Ukrainian side and was told that in an hour and a half I would arrive in Lviv where I was to join my friend Olesya, the very one who prompted me to come here and now.

To follow were days of peeping into courtyards of old Lviv, walking the cobble streets, climbing onto the roofs opposite the former Golden Rose synagogue in Staroyevreyska street, wandering in the Lychakivskiy Cemetery reading mournful tributes inscribed in Ukrainian, Russian, German, Polish, Armenian, Latin. And of course there were poetry readings, music and late night discussions. Olesya bought a newly printed Ukrainian edition of Debora Vogel poetry with illustrations and that was the start of our collaboration, our voyage to explore text, images and sounds of Vogel’s work and life.

Debora Vogel was born in 1902 in Burshtyn (Galicia) in a non-observant, Polish-speaking home. During WWI the family fled to Vienna and later moved to Lviv. She traveled extensively in Europe and was part of the vibrant Polish modernist scene of the interwar period. It was in Lviv where Vogel wrote poems in Yiddish in the 1930s that reflected the radical and minimalistic outlook that all art aspired toward during this period in history. Her experiment in poetry was mostly about fusing poetry and art. She called this technique ‘white words’ and described it as an attempt to “create a new lyric poetry of the urban condition”. Together with her husband and son, Vogel was killed in the Lviv ghetto in 1942.

Around 1930 Debora Vogel became acquainted with the Polish Jewish writer and artist Bruno Schulz who was as yet unpublished. The two developed a close relationship and carried on an intensive correspondence. It was Fogel who encouraged Schulz to develop the lyrical postscripts to his letters, passages that became the basis for his first publication “Cinnamon Shops” (1934), published in English as “Street of the Crocodiles.” Half a century later brothers Quay created a stop-motion animation based on this short novel. Ironically, Vogel is better known today for her connection with Schulz than for her own unique and innovative poetic vision. Very little of her work has been translated into Russian and Ukrainian, none into English.

The first letter (survived and translated into Russian by Dana Pinczewska) Vogel sent to Schulz starts like this:

21.V.1938 Бруно! Декорация этого письма – Сколе.

Bruno! The background scenery of this letter is Skole.

And here I am, on the early morning train from Lviv to the Carpathian mountains, not yet knowing of this letter, following my own story reconnecting with the places of my childhood. I doze off and when I open my eyes I am blinded by the sun breaking through the clouds, next what I see is the station building with ‘Skole’ on it exactly how I remember it when I was a kid.

The letter continues:

Твое последнее письмо вернуло мне давний образ осеннего ландо, на котором мы должны были вместе уехать в красочную страну. Запах путешествия обладает неотразимым очарованием и странным образом всегда ассоциируется с образом кого-то другого, спутника. Затем оказывается, что хорошо быть одному, совсем хорошо быть более чем одному — быть одиноким, оставленным, безнадежно отданным на милость оставленности и бездомности. Тогда «видится» хорошо.

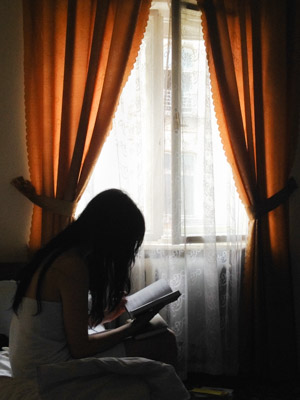

Your last letter brought back the distant image of the autumnal landau which should have taken us to a beautiful far away land. The smell of the journey has an irresistible charm, and strangely, it makes me think of someone else, of a companion. But then it turns out that it is so good to be on my own, and what is even better is to be alone, deserted, left at the mercy of abandonment and homelessness. Then one can ‘see’ well.