Chapter 5 – Inheritance

My grandfather’s historical way of thinking was peculiar. His method was open, invitational, associative – in many ways that of an artist. And to me it feels meaningful that as his granddaughter, I’m inheriting a bundle of things – his silences, his methods and his inner drive to interpret the experiences of the 20th century. I would liken his method to the play of the surface of water. Here is an excerpt from durational contemplative pieces shot by Jason Francisco on our research trip together.

One day I find an epigraph that I previously overlooked in my grandfather’s first book. He dedicated it to his uncle David perished in the Stalin purges, to his mother and David’s son killed in the Holocaust in Crimea. What happened was in his living memory. Mourning his losses, grieving on his behalf now, enables me to construct a tangible link to the past no one talked about. My grandfather’s silence stands as an epigraph to my search the way the epigraph to his mother’s and uncle’s death stands to his intellectual life.

For my generation, the point of origin is not the direct devastation of the revolution, the wars, the atrocities, the repressions, the communist years. My generation is near but did not go through these worst, most devastating decades. Mine was not the generation most directly exposed, did not grow up with a ready repository of stories. And so the tasks of my generation are different. Certain kinds of historical traumas precisely require generations to understand. If surviving was the defining task of the older generation, creating meaningful forms of inheritance seems like the defining task of mine. My generation, unlike the preceding generations, must reconstruct events from ‘incomplete, oblique, cryptically coded, and elusive knowledge, only a fraction of the story’ as the Canadian writer Alison Pick discloses.

Genealogical research is more than filling blanks on the family tree. It is the search for others, for their experiences that made us ‘us’, for the psychic forces that move through generations that have an immediate effect on our lives. It is the study of the prehistory of self. The discovery of the deep self that existed before we were born.

There is another aspect to inheritance. I’m thinking about Aizenbergs, Blumenfelds, Gefters, Goreliks, Guttzeits, Drabkins, Erenbergs, Katznelsons, Mermelsteins, Tsirlins. At the end of the 19th century all of them lived along the eastern border of the Pale of Settlement, what is present-day Belarus and Ukraine. In the early 1900s some followed the American dream, some – the Eretz Israel dream, and some witnessed the Russian Revolution. Less proactive stayed behind and got killed because they were Jews. Some perished in the Stalin purges, at the WWII front and during the Leningrad siege from starvation. Some survived the decades of the Soviet regime and stayed, some moved to the US and Israel. Yet, no one returned to Europe, where our ancestors lived for centuries. Possibly, this is my way. This is how I feel and what I have pursued for the past 20 years.

I’m thinking about Jewishness and what it is to be Jewish. It is a mixed phenomenon, Jews escape categories. Jewishness has different expressions – religious, cultural, historical, political – but is not reducible to any of those. The person who grows up without a religion is not deficient in Jewishness. Those born in Warsaw or Sao Paulo are not more or less Jewish than the ones born in Addis Ababa or Jerusalem. What is both beautiful and difficult about being Jewish is that it is a dynamic thing. Every Jew has a different balance of Jewishness.

For me it is a certain way of being in the world. To inherit Jewishness means to find my way into and through it for myself.

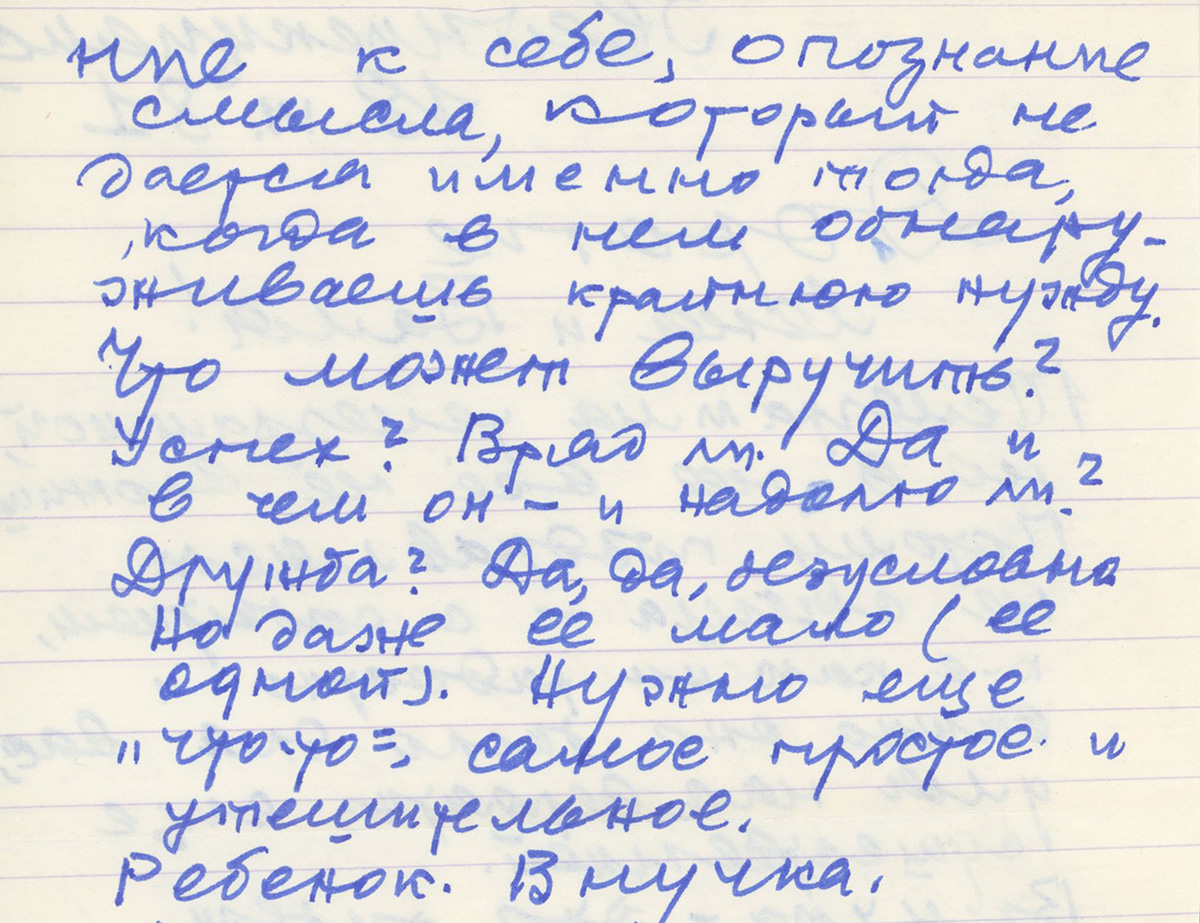

I don’t know how to describe the emotions I feel when I find a letter that my grandfather addressed to my parents when I turned 1. He writes: “My granddaughter is my legacy, she is a justification for my entire life. What is left? The return to myself, looking for meaning, that I cannot find when I need it the most. What could help? Success? Unlikely. And even if that – how long for? Friendships? Yes, yes, undoubtedly so. But even that is not enough. Something else is needed, something very simple and comforting. A child. A grand-daughter.”